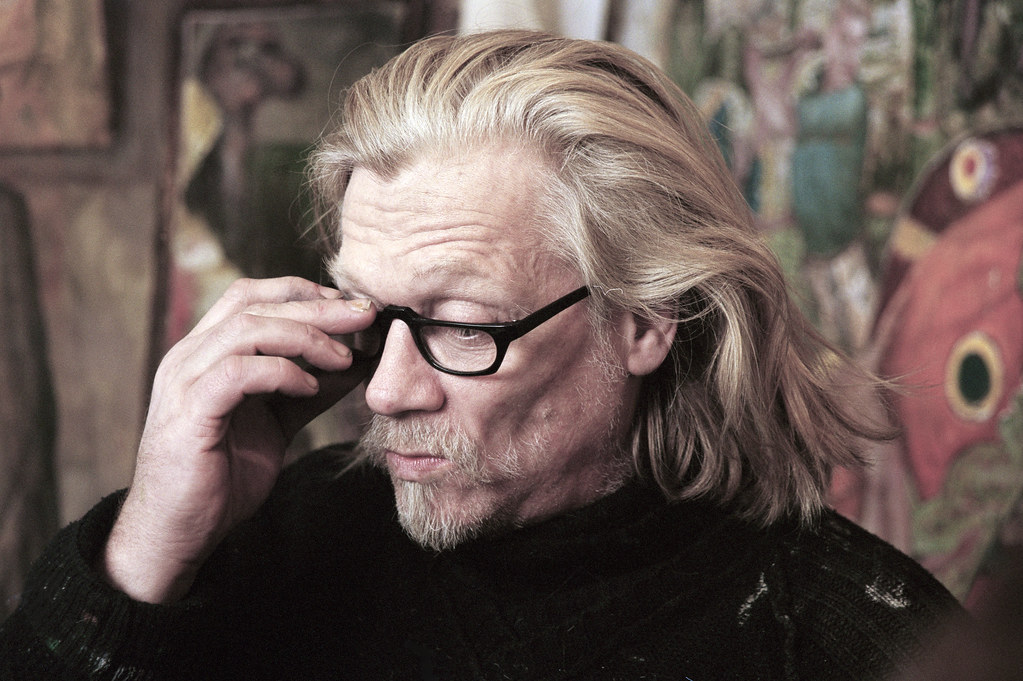

‘I think I became less interested in art, conceptual versus figurative, that kind of thing, and I became more interested in thinking about why things are the way they are…’ [1] – Steven Campbell.

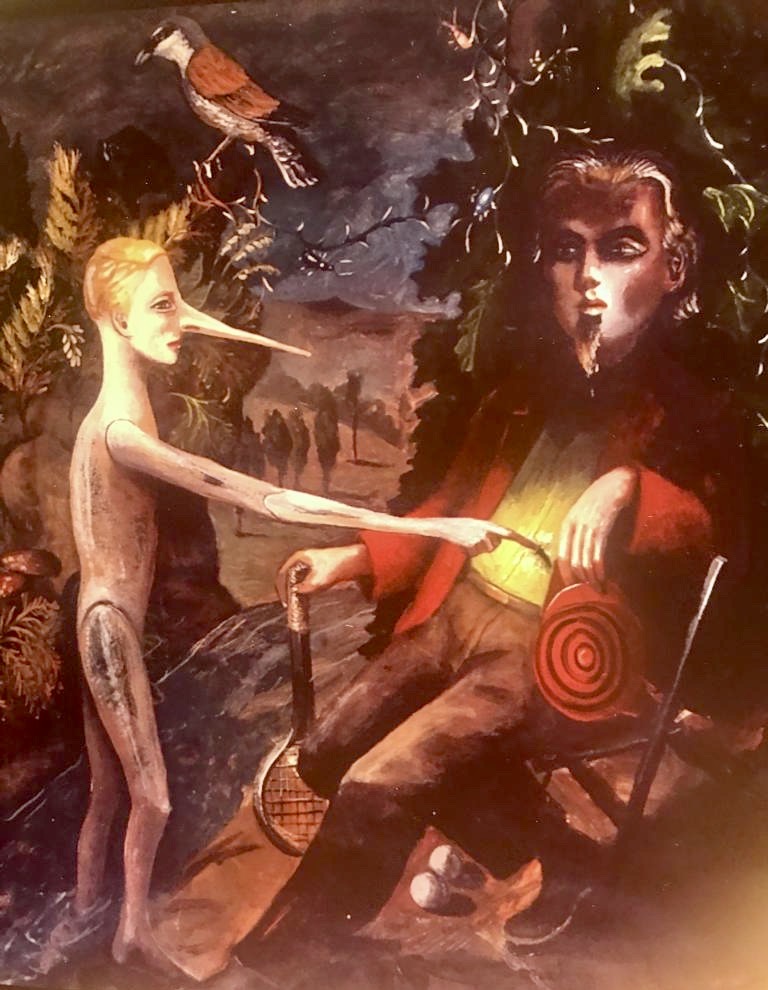

Steven Campbell’s work displays a persistent fascination with illusion and the levels of reality that exist within a painting. By their nature, figurative paintings are flat and static, showing fixed and illusory worlds, the subjects trapped in time, caught in the confines of the canvas. As the writer Duncan MacMillan observes, while Campbell’s characters ‘innocently explore the apparent freedom of the world they inhabit, they run up against its limits, and, unconsciously, burlesque the limitations of the painter’s art and so of life itself.’ [2]

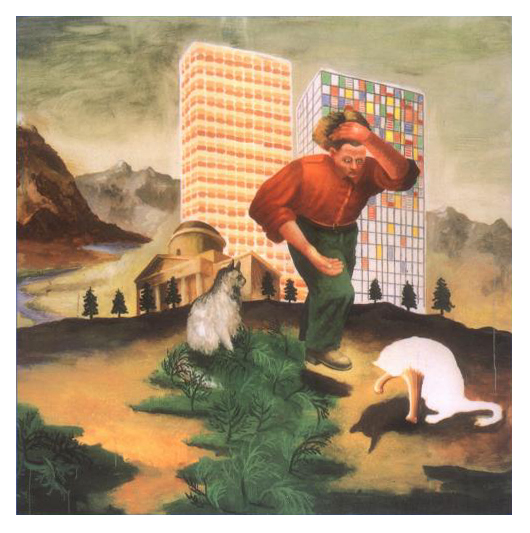

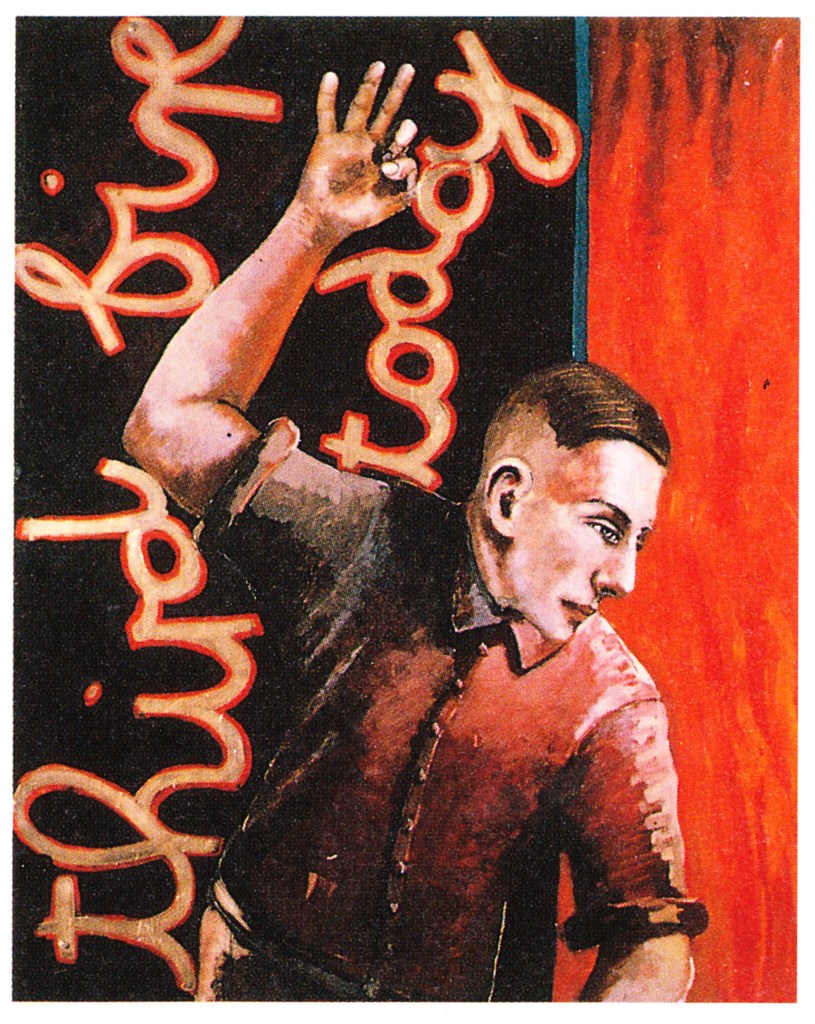

In the above painting, The Man who climbs Maps, we see the character of the Lost Hiker. Like so many of Campbell’s characters, the Hiker has strayed from his path, and in desperation, attempts to climb his map as if it were a cliff face.

Here, Campbell invites the viewer to consider the nature of painted space. In the world of painted narrative, everything is two-dimensional and on the same plane of existence: the flat illustrations on the map essentially no different from the surrounding landscape and the Hiker himself [3]. Confused, the character mistakes the map for the territory as he embarks on his expedition.

Another interesting detail in the above painting is the signpost on the bottom left. Such signposts appear often in Campbell’s work, indicating that the characters are suspended between different places, in a sort of limbo or no-man’s land. They never reach their goal or destination, and are trapped in an illusory world that frustrates them at every turn.

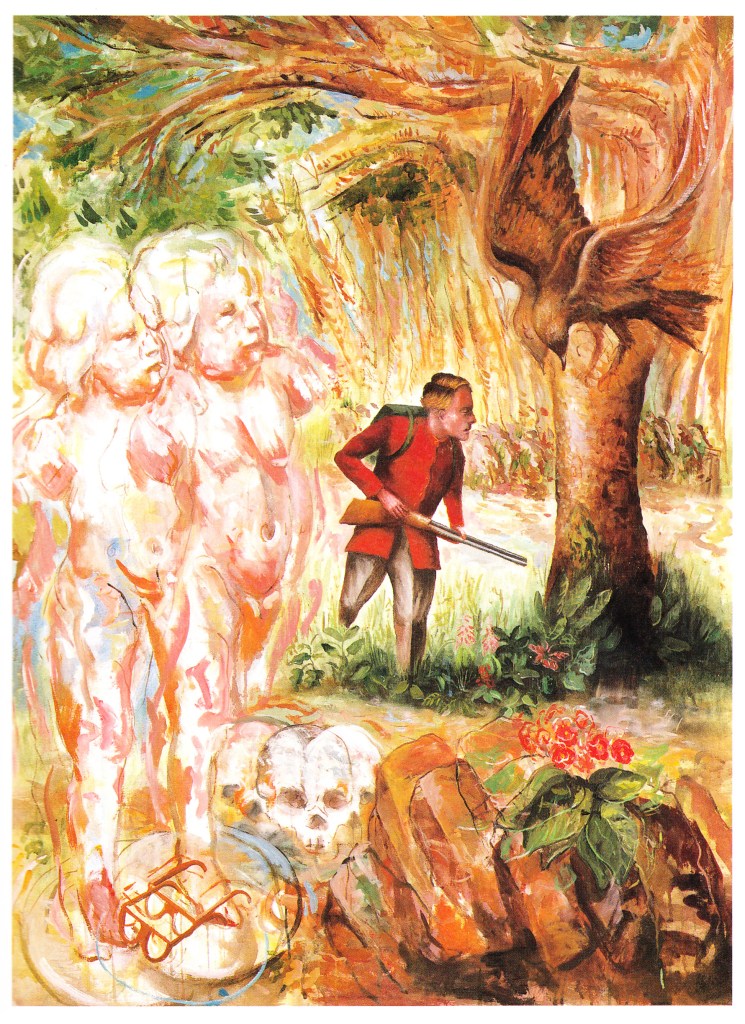

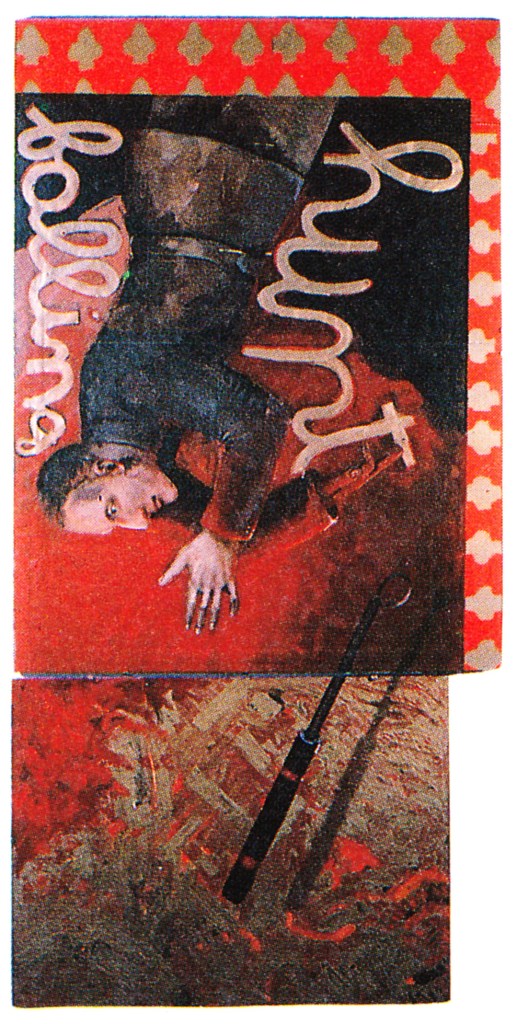

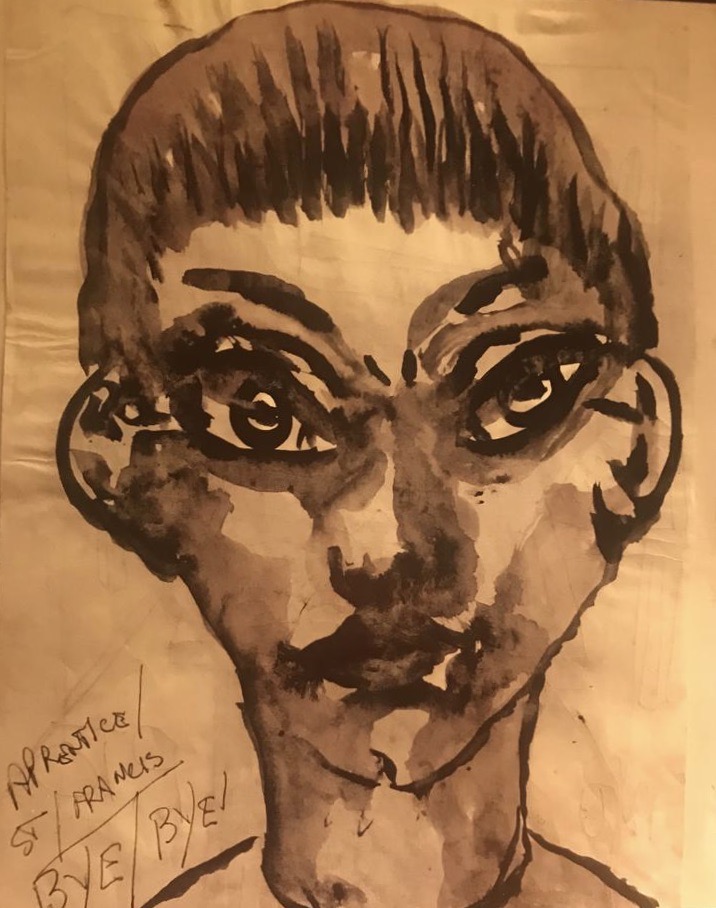

In Young Camper Discovering a Grotto in the ground, Campbell further explores the illusion of painted space. It has seven figures in different scales, and in this crowded painting, we’re not entirely sure who the camper is, and it may in fact be all of them.

The perspective here seems intentionally confusing: we don’t know whether characters are in the background or foreground, and are finally led to conclude that each figure inhabits his own ‘grotto’ of space in the picture-plane. [4] These grottos overlap in a sort of mosaic, confusing the viewer, and apparently confusing the characters themselves. Campbell has taken images that may have made pictorial sense, and then dismantled, restructured and overlapped them, to demonstrate that representational painters deal only in illusion.

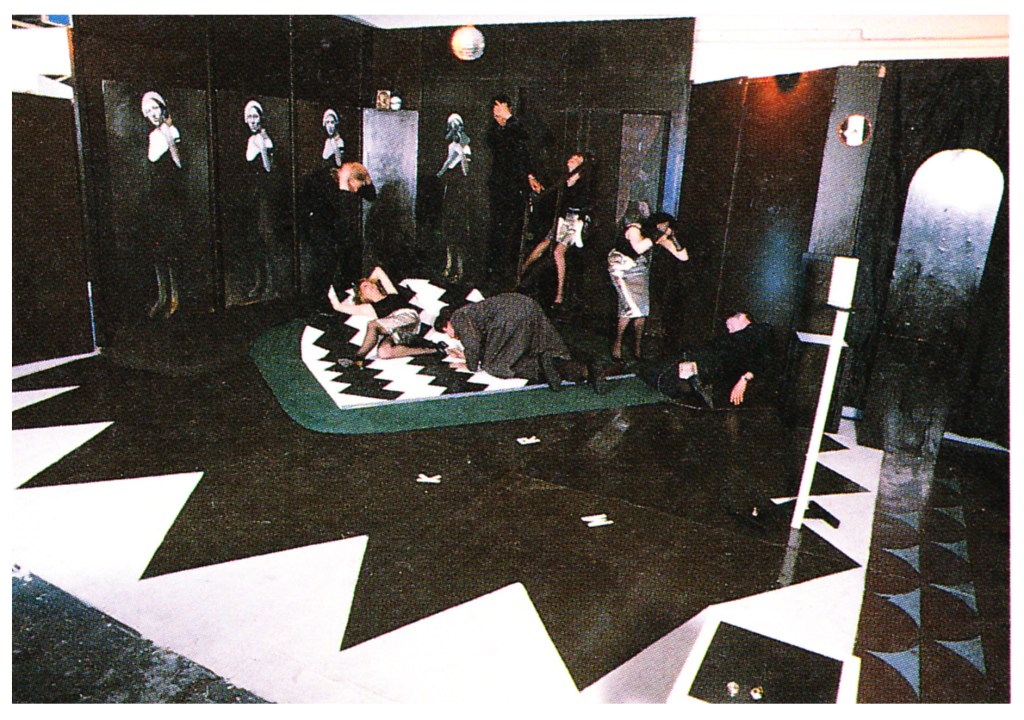

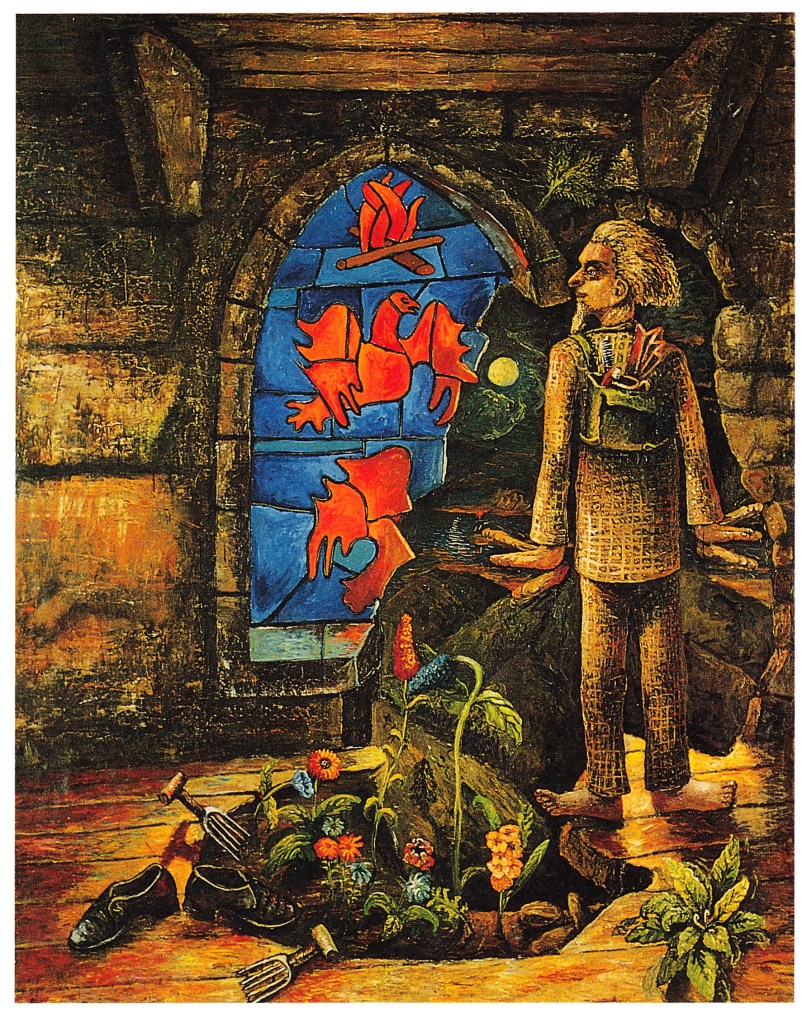

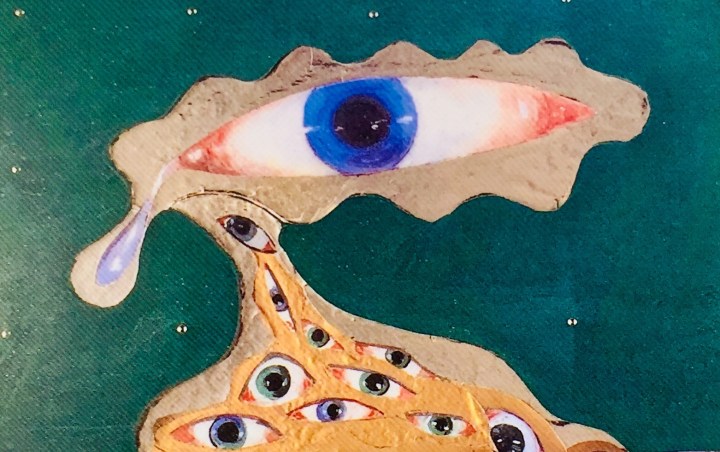

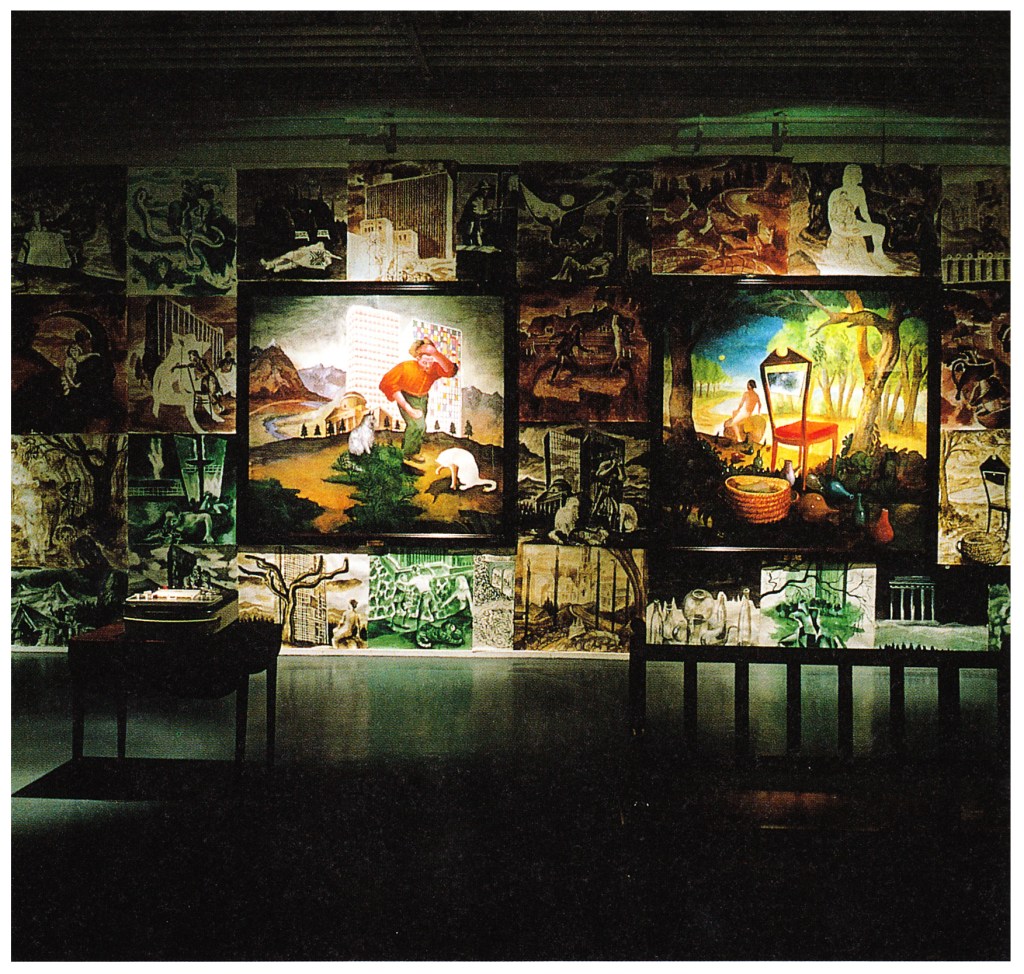

Campbell made this a major theme of his work in an exhibition at the Third Eye Centre in Glasgow (now the Centre for Contemporary Art) in 1990. The show questioned received notions about reality, often in a humorous way.

In many of the paintings, certain figures or objects were missing, showing only white canvas in the place that they had once been or were intended to be.

The above painting Not you as well, Snowy, shows a young man returning home to see that his cat has also undergone this horrible metamorphosis, snatched from reality to leave only a white silhouette in its place [5]. Something which, to us, is only a bit of blank canvas in the middle of the picture plane, becomes the shape of this poor character’s missing cat – snatched away into the ether, leaving only his shadow and his paws. In this disturbing yet humorous way, Campbell questions the reality of our own world.

Sources used in this blog post: The Paintings of Steven Campbell: The Story So Far/ by Duncan MacMillan/ Publisher: South London Gallery/ Date Published: 1993 (p.27, 36, 37, 65 & 108). If you’re wanting to find out more about the work of Steven Campbell, we would highly recommend getting this Duncan MacMillan book, which looks at Campbell’s work in a great deal of depth.

Footnotes:

[1] – p.108 / The Artist in Conversation/ Steven Campbell describes his recent paintings in conversation with Duncan Macmillan, Bollochleam, Wednesday 10 March 1993 / The Paintings of Steven Campbell: The Story So Far/ by Duncan MacMillan/ Publisher: South London Gallery/ Date Published: 1993

[2] – p.36 / The Paintings of Steven Campbell: The Story So Far/ by Duncan MacMillan/ Publisher: South London Gallery/ Date Published: 1993

[3] – p.27 / The Paintings of Steven Campbell: The Story So Far/ by Duncan MacMillan/ Publisher: South London Gallery/ Date Published: 1993

[4] – p.37 / The Paintings of Steven Campbell: The Story So Far/ by Duncan MacMillan/ Publisher: South London Gallery/ Date Published: 1993

[5] – p.65 / The Paintings of Steven Campbell: The Story So Far/ by Duncan MacMillan/ Publisher: South London Gallery/ Date Published: 1993